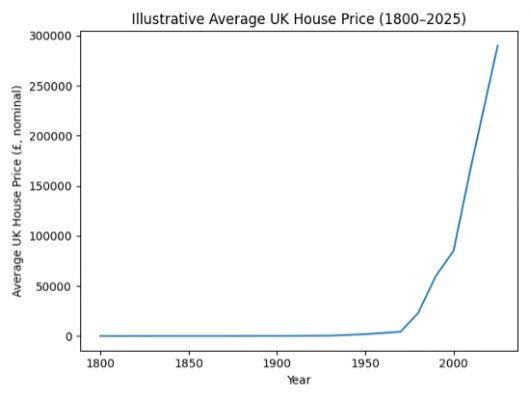

Britain is approaching a demographic watershed. As the Resolution Foundation warns, deaths are poised to exceed births for the first time outside exceptional years, driven overwhelmingly by collapsing fertility rather than rising mortality. The UK’s total fertility rate has fallen to around 1.4 children per woman—far below the replacement level of 2.1 and less than half the level seen in the 1960s. The implications for public finances, labour supply and social cohesion are profound.

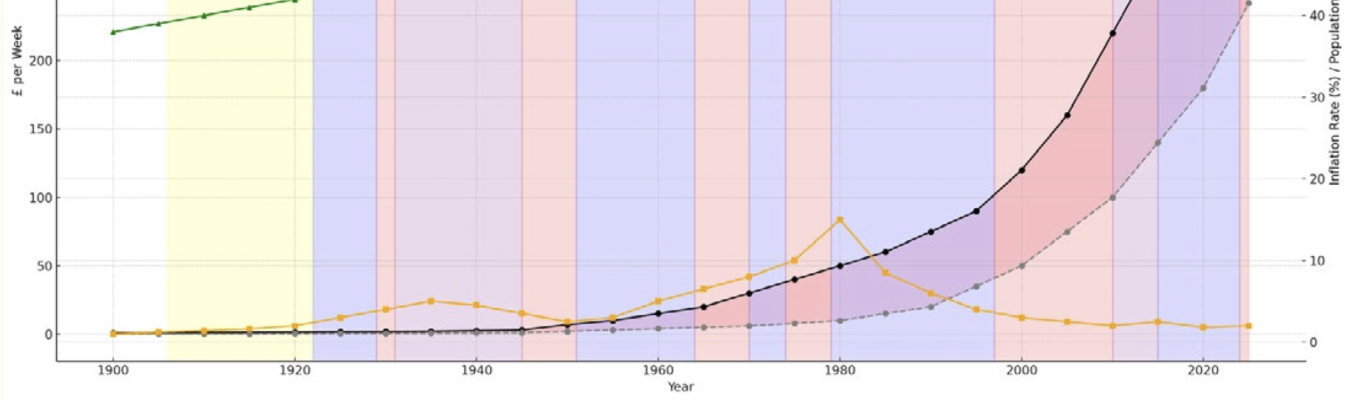

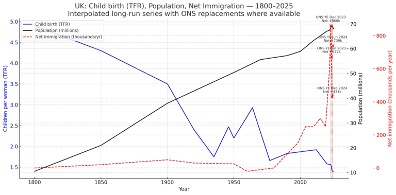

The long-run housing trend provides essential context. For more than a century, average house prices in Britain rose only gradually. Figure 1 below shows how prices remained broadly stable until the mid-20th century before accelerating sharply after the 1970s. This inflection marks a structural break in affordability, not a natural economic evolution.

This housing shift directly precedes Britain’s demographic reversal. Figure 2 makes the relationship unmistakable. As fertility trends steadily downward across the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, net immigration—historically low for much of the modern era—rises sharply, surging after 2000 and accelerating further after 2020. Population growth is now sustained almost entirely by immigration rather than births.

The sale of council houses under Margaret Thatcher MP and PM expanded home ownership and was politically transformative. The failure was not the policy itself, but the decision not to recycle the proceeds into new social housing. Over time, the affordable housing stock shrank while demand hooking into a growing population increased. Prices detached from earnings, rents absorbed ever greater shares of income, and housing insecurity became normal for younger generations.

These conditions delay household formation, postpone partnerships and suppress family size. Immigration has become a structural substitute for domestic births, not because of cultural preference, but because Britain priced family life out of reach.

Figure 1: Long-run UK Average House Prices (1800–2025)

Figure 2: UK Fertility, Population and Net Immigration

Summation: Population Growth, Housing Demand and Market Balance

Continued population growth, whether driven by natural increase or sustained net immigration, inevitably raises demand for housing. In a market where supply is structurally constrained, this demand pressure translates directly into higher prices and rents. Left unchecked, rising population numbers therefore risk reinforcing the very affordability crisis that suppresses family formation and drives demographic imbalance.

This dynamic cannot be resolved by the private housing market alone. The speculative incentives of the housebuilding and development industry tend to prioritise scarcity, land banking and higher margins over long-term affordability. Without a counterbalancing force, housing supply becomes insufficiently responsive to social need.

Sustained investment in social housing is therefore essential. By expanding the stock of genuinely affordable homes, the state can relieve pressure on the wider market, moderate price inflation, and reduce the extent to which housing outcomes are controlled by developer interests rather than public policy objectives. Social housing does not crowd out private provision; it stabilises it.

If Britain is serious about restoring affordability, supporting family life and achieving a sustainable demographic future, social housing must once again be treated as core national infrastructure. Without it, population growth will continue to feed housing inflation, and the cycle of delayed families, falling fertility and rising dependency will remain unbroken.

ADRIAN HAWKINS OBE

Chairman – biz4Biz

Chairman – Hertfordshire Futures Board

Chairman – Stevenage Development Board

Chairman – Hertfordshire Skills & Employment Board